Actions and Puzzles

In the video game Genshin Impact there are a number of fun puzzles that can be played to unlock rewards. These puzzles can be solved with some patience; this post is going to be about how we can also solve it with some mathematics! I am going to discuss a particular type of puzzle that appears in the game of which varients appear in other video games. Figure 1 displays one such puzzle that makes for a good working example.

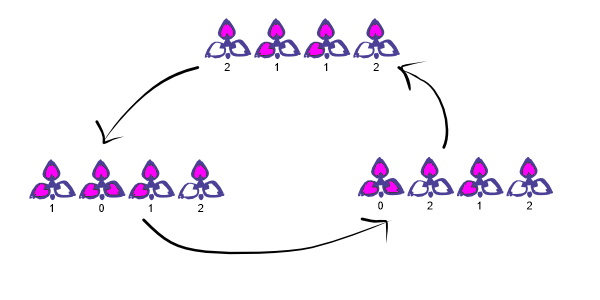

This puzzle involves a set of blocks, each of which has a clover for which a number of leafs can light up. Hitting one of the blocks causes one or more (neighbouring) blocks to change to a different number of lit leafs. For instance, in this puzzle, hitting the far left block results in the two left-most blocks to light up one more leaf as depicted in Figure 2.

The goal is simple: light all the leafs of all the blocks. The state of a fixed block is described by the number of leafs lit or, equivalently, the number of leafs unlit. We will take the latter interpretation for mathematical convenience. In this particular puzzle, the block can either have zero (\(0\)), one (\(1\)) or two (\(2\)) leafs unlit. The state of the entire puzzle is thus described by a sequence of four of these integers. For instance, the state in Figure 1 is described by \((2, 1, 1, 2)\). The set of all puzzle states is \(X = \{0, 1, 2\}^4\).

The action of hitting the far left-most block increments the number of lit leafs in the leading two blocks by one. If a block was at three lit leafs, then that block returns to one lit leaf. Denote this action of hitting the far left-most block by \(g_1: X \to X\), which is a map that goes from the current state of the puzzle to the subsequent state of the puzzle. If \(c\) and \(d\) are the initial states of the right-most blocks, then repeated application of \(g_1\) to \((2, 1, c, d)\) results in, \[ \begin{aligned} (2, 1, c, d) &\mapsto (1, 0, c, d),\\ (1, 0, c, d) &\mapsto (0, 2, c, d),\\ (0, 2, c, d) &\mapsto (2, 1, c, d). \end{aligned} \] The action decrements the count of the first two blocks since our state captures the number of unlit leafs. There is a cyclic behaviour here. It is depicted in Figure 3.

Mathematically, letting \(0\) denote the identity action (the “do nothing” action), the cycle is described by, \[ g_1 + g_1 + g_1 = 3\,g_1 = 0. \] All of the other actions in this puzzle have this property. Repeating an action three times will return us to the original state prior to the initial action. This is a convenient property that allows us to determine something critical: the inverse of \(g_1\) — the action \(-g_1\) that reverses an application of \(g_1\) — is just the repeated action of \(g_1\) twice. That is \(-g_1 = 2\,g_1\).

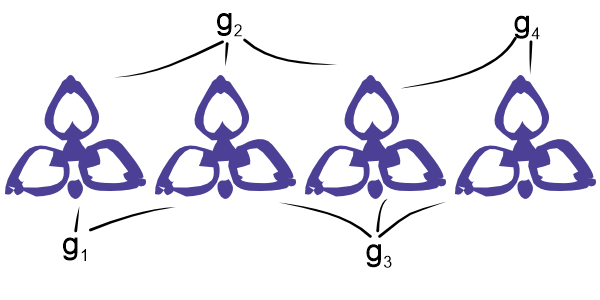

Let \(g_2: X \to X\) denote the second action (hitting the second block from the left): this action decrements the first three blocks from the left by exactly one. Likewise, define \(g_3\) and \(g_4: X \to X.\) The actions decrement the states pointed to in Figure 4.

We shall call \(g_1\), \(g_2\), \(g_3\) and \(g_4\) the primitive actions. Their inverses are also easily defined by repeating the same action twice. The primitive actions can be described by a sequence of four integers describing which states to decrement, \[ \begin{aligned} g_1 &= (-1, -1, 0, 0),\\ g_2 &= (-1, -1, -1, 0),\\ g_3 &= (0, -1, -1, -1),\\ g_4 &= (0, 0, -1, -1). \end{aligned} \] and they can be combined by adding component-wise. For example, \(g_1 + g_2\) is, \[ g_1 + g_2 = (-2, -2, -1, 0). \] If we combine the observations that:

- each action repeated three times returns the original state,

- the actions associate: \((g_1 + g_2) + g_3 = g_1 + (g_2 + g_3)\),

- the actions commute: \(g_1 + g_2 = g_2 + g_1\),

then we can see that the complete set of actions is the (additive) group \(\mathbb{F}_3^4\): the additive space of \(4\)-vectors of elements in the field of integers mod \(3\).

In fact, we can endow the space \(\mathbb{F}_3^4\) with a vector space structure if we take the ground field to be \(\mathbb{F}_3.\) Critically, the primitives actions generate the vector space \[ \mathbb{F}_3^4 = \langle g_1, g_2, g_3, g_4 \rangle, \] and the state of our problem can be described as an element of this space, i.e. \((2, 1, 1, 2) \in \mathbb{F}_3^4.\) This means we can now cast the problem of solving the puzzle as a linear algebra problem. Fundamentally, we want to find a sequence of actions in \(\mathbb{F}_3^4\) that transform the state \((2, 1, 1, 2)\) into the zero state \((0, 0, 0, 0)\) which corresponds to all the leafs being lit. To start, we should figure out if we can write \((2, 1, 1, 2)\) as an additive combination of the primitive actions \(g_i.\) The linear algebra problem to solve is, \[ \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & -1 & 0 & 0\\ -1 & -1 & -1 & 0\\ 0 & -1 & -1 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & -1 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \\ d \end{pmatrix} \] Solving this system results in \[ (a, b, c, d) = (-3, 1, 1, -3) = (0, 1, 1, 0) \in \mathbb{F}_3^4. \] That is, \[ (2, 1, 1, 2) = (g_2 + g_3)\,(0, 0, 0, 0) \]

Since we now know that the current state is arrived at by applying the action \(g_3\) followed by action \(g_2\), we merely have to invert these operations. Recalling the earlier discussion that \(-g_2 = 2\,g_2\) and \(-g_3 = 2\,g_3\), conclude that, \[ (2\,g_3 + 2\,g_2)\,(2, 1, 1, 2) = (0, 0, 0, 0), \] solving the problem. This suggests that hitting the second and the third block exactly twice (in no particular order) will solve the puzzle. In Figure 5, we see the result of applying the second action twice. It should be immediately clear that the third action repeated twice solves the puzzle.